A new abolition movement

Regan King, Campaigns Officer, looks at the parallels between the movement to abolish slavery and the modern-day movement to abolish abortion.

Anniversary of Abolition

2017 marks 210 years since The Abolition of The Slave Trade Act (1807). The act put an end to the legal slave trade within the British Empire, in particular the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery itself remained legal in the British Empire for another 26 years. It was then that the Slavery Abolition Act (1833) finally came into British law.

The slave trade and slavery were accepted, legal, and in many circles celebrated institutions. Some considered it a right, others considered it an evil, but one that was necessary. Few saw the slave trade and slavery for the immense evil it was. Christian leaders of the land were either silent on the subject or shut out by the noise of slavery’s violent proponents.

Enter the Clapham Sect, a group of Christians (mostly based out of Clapham) whose primary purpose was to see the slave trade and slavery abolished. This group, considered radical and dangerous by many, was a motley odd-bod crew that included an ex-slave-trader turned clergyman (John Newton), a brewer (Thomas Buxton), some MPs (most notably William Wilberforce), a writer (Hannah More), and various church leaders (including Charles Simeon) among others. The members of the Clapham Sect devoted themselves to the cause of abolishing the slave trade and used their spheres of influence to impact public opinion, channelling much of their wealthy into the cause.

How slavery was exposed and eventually abolished

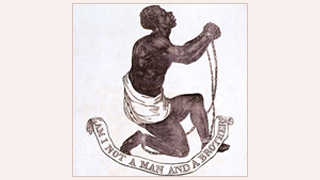

What many forget about the Clapham Sect is their use of graphic visual aids to impact the debate on slavery’s abolition. The Josiah Wedgwood porcelain cameo of a chained slave asking ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’ became a visual symbol of the abolition movement. Thomas Clarkson found the use of visual aids impacted people more than words alone and would hold meetings displaying the grim instruments of torture and restraint used on slaves, publishing engravings of the same. The first hand biographical account of an ex-slave, Olaudah Equiano, was promoted widely.

It was Clarkson’s work and such first-hand details that appear to have influenced William Wilberforce the most in his representation of the abolition cause in Parliament from 1787. Wilberforce is said to have taken unwitting dignitaries on cruises around the Thames with the purpose of exhibiting slave ships with their odour of dung, disease, and death.

While many were not best pleased by graphic visuals and first-hand experiences of slave ships, these were crucial to the abolition of the slave trade in 1807. Wilberforce continued to devote his life in calling for slavery’s total abolition in Parliament until 1826 when ill health forced him to retire. Outside of Parliament, Wilberforce continued to campaign until, finally, slavery was abolished in 1833. Three days after this penultimate Act was read in Parliament, Wilberforce’s life’s mission accomplished, he died.

A new abolition movement

Once again our society is tarnished by systemic acceptance of a grave evil. That evil that is abortion. Abortion takes the life of pre-born children in the mother’s womb before the child has so much as been able to take a first breath. With heart beating from around 21 days from conception, abortion sees the pre-born’s life savagely ripped out of its mother’s womb, through medical expulsion or a dismemberment and vacuum process. In some cases, the child is not even dead until some moments after its removal from the womb, in which case it is left to expire, its cries ignored.

The pro-life movement is the modern-day abolition movement. Viewed by many in society as a movement of crackpots and insurrectionists, the pro-life movement strives to fulfil a mission that even some of its adherents feel is impossible: the end of legal abortion.

Among front-line advocates for the abolition of abortion in Britain is Abort67. Taking inspiration from Thomas Clarkson and William Wilberforce, Abort67 seeks to raise abortion awareness by publicly displaying real images of aborted babies.

When I (and I am sure others) see Abort67’s images a string of words enters my mind.

Disgusting. Disturbing. Grim. Gruesome. Horrifying. Shocking. Terrible. Vile.

The very words that describe abortion.

I do not like Abort 67's pictures of aborted babies. Abort67 does not like their pictures of aborted babies. No one likes them. That is precisely why they must be shown. The pictures show abortion for what it is - a sad, horrifying, bloody mess of what was a distinct, living, whole, human being.

In the past week, many celebrated Halloween by going to watch horror movies filled with gore and graphic violence and didn’t bat an eyelid. Why is it that many of the same people respond in horror and even anger at the abortion pictures? Because, unlike a horror movie, the pictures convey truth and tragic reality that we would rather not think about and we be more comfortable ignoring.

The pictures are supposed to make people uncomfortable. They are supposed to shock. They are meant to help people re-evaluate their own ideas. If someone feels sick at seeing a picture, perhaps they will become sick at the idea of abortion as many of us are. If the pictures make people angry, perhaps they will respond as the people of Wilberforce and Clarkson’s day and express their anger in petitions and in the voting booth by speaking out for pre-born life.

27 October 2017, marked 50 years since the Abortion Act (1967) received its Royal Assent. In the 50 years of legal abortion in the UK, more than 8 million lives have been lost. 8 million human beings with great potential. 8 million human beings the value of whose loss is impossible to measure. Potential law-makers, leaders, doctors, inventors, cancer researchers, technicians, scholars, city-builders, discoverers, or simply healthy members of society. All potential snuffed out by a choice and the abortionist’s tools.

To commemorate the Abortion Act’s 50th Anniversary, Abort67 gathered around 100 people to take part in the UK’s largest abortion display. Located around the perimeter of Parliament Square, abolitionists sought to challenge the public and politicians to call for an end to abortion in the UK.

Many were angry and expressed disagreement, shouting empty slogans like ‘My body, my choice!’ failing to see that it is not the woman’s body being robbed of breath and any life in abortion. Others were cautious, probably disturbed by the reality of abortion, but not really wanting to do or say anything against it lest they betray their profession of moral relativity and subjectivism. ‘Morality is contextual.’ one man said, before quickly disengaging.

Others were thoughtful and seemed grieved to see the reality of abortion. Perhaps even in those angered or cautious, a seed was planted that will produce doubt and eventual grief that sees abortion for the evil it is.

Last week Wendy Savage claimed that legal abortion was the ‘greatest public health success of the 20th century’. Our prayer and goal is that one day legalising abortion will be viewed more objectively: one of the greatest evils and tragedies of the 20th and 21st centuries. But an evil that was successfully quashed by a diverse band of abolitionists who wouldn’t be content to leave it unexposed.

It is time we expose abortion for the horror it really and truly is.